History doesn’t just happen. Take, for example, how New South Wales came into being as a colony; as an oversimplification it is evident that it was the British Government’s objective the to establish a penal colony and a settlement, but how the land, the country, was perceived was then a consequence of the processes and actions of settlement as these fed into British world views. The authorities in Britain, and the settlers, could see a country alien, and seemingly unowned, that could be claimed and developed in the name of a monarch and seat of empire half a world away.

There are many reasons for making gardens, as indeed there are many approaches to thinking about, looking at and understanding gardens. And, of course there are multiple forms of gardens and gardening. These are not simple statements. Just think about how gardens have changed over time in their forms and the plants that are in them, that is the planting palette. I am thinking only of gardens in Australia since white settlement. The scene becomes even more complex if we take into account gardens of other countries – so I won’t.

The actual subject of my talk is the book, Gardens of History and Imagination. It is a collection of essays that I co-edited, by different authors who chose to take quite eclectic approaches in examining the role of gardens in the history of the colony. The variety in choice of approach is unsurprising given, not only the very different backgrounds of the writers, but the kaleidoscope of perspectives that can be taken to thinking about, making and appreciating gardens. The work, which is a project of the New South Wales chapter of the Independent Scholars Association of Australia, was published to chime with the celebrations of the bicentenary of the Royal Botanic Gardens. Interestingly, the ‘Royal’ was only added at the time of the young Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Australia in the early 50s.

The focus of this work is on 19th-century News South Wales but the resonances extend beyond that time and that place, reflecting different ways of seeing and being in the world. There are shafts of personal histories but the collection is significant in revealing the social importance of garden-making. Our interest is on ornamental or pleasure gardens: while sustenance gardens were clearly critical in the early days of the colony, and remain important, they do not tend to carry the same social messages.

The other day I came across a quote, drawn originally from a work of T S Eliot. In 1921 he wrote In the Sacred Wood, which is a collection of his essays on poetry and criticism, that ‘(we) will not think it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is dictated by the past’. This seems to give significant weight to perceptions and ways of thinking but it also has implications for action. Nowhere can this be better expressed than in heritage. What we value and why are assessments of today, and that heritage value informs present actions –– or at least that is the principle. It is the thread that runs through Stuart Read’s essay.

I thought that I would trawl through the book to give you an idea of its contents and so I shall start with Stuart’s chapter.

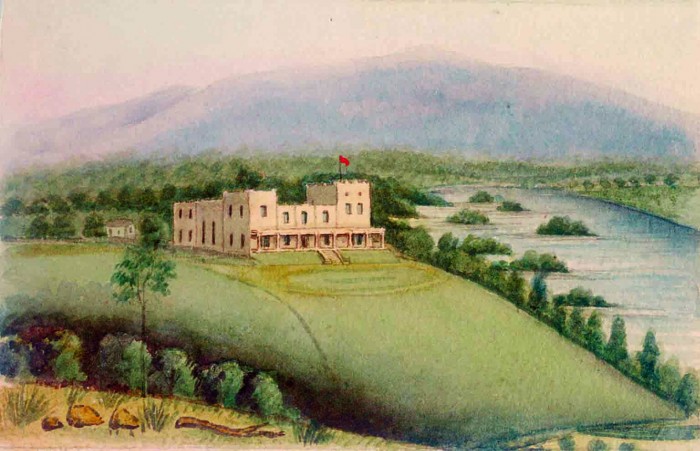

He takes as his subject riverine houses and gardens of the elite in 19th century Sydney. He identifies many grand estates that we recognise as rich in history and that we have taken steps to conserve, but sadly, the principal often founders and he also rues the destruction of much of that history and the continuing risk facing so much else. I point out here that while these estates have at their centre a building –– or buildings ––no less do they include the surrounding garden expressing cultural and personal values as palpably as the house; They certainly carry messages of social class.

Perhaps at this stage I should own up to having no horticultural expertise or background. I am an anthropologist, and many of you may wonder why I am so absorbed in garden-making, gardens and how they are perceived. The reason is straightforward: gardens, garden-making and their social significance is as much about people as it is about plants, and each essay in the book reveals that dynamic relationship.

There is a well-enough cited aphorism that the past is another country. While this may imply that history is essentially beyond our ken, looking at garden-making in the development of the colony, it comes with more than a ring of truth. While some early settlers in New South Wales came burdened by their past –– obviously the case with convicts –– others were liberated from it. Convicts aside, this applied to free settlers whose prospects in Britain were limited, as well as to military personnel. The futures of all were prefigured by the lives they had lead in Britain. Whether they came with memories they were reluctant to abandon, or hopes on which to build, the new land offered opportunities for the settlers and emancipated convicts to do things differently. It was in making a garden, albeit expressing British values, that many newcomers were able to refashion a life and a new identity, and in this way to grow a colony. That history is inscribed in the landscapes of today; we are its stewards. Your interest and concerns reflect that.

In her chapter ‘Exhibiting Gardens’ Ailsa McPherson explores the establishment of horticultural societies in the colony, with a particular focus on their exhibitions: these displays revealed the social complexities of the relationship between professional horticulturalists and amateurs –– the latter usually gentleman practitioners. Private horticultural displays appeared early in the 19th century but it wasn’t until 1838 that elaborate public exhibitions were staged. Ailsa writes of the ‘enduring influence’ of Britain; of how the concept of a garden was directly associated with ‘an often idealised memory of a British home, although realising that nebulous idea all too often collapsed when faced with colonial actuality.’ Yet it remained a powerful force. Images of horticultural exhibitions that Ailsa has selected, drawn from the Illustrated Sydney News and other media, bear a clear stamp of fashionable British society. Images of the crowds milling around and inside the Exhibition Building not only reflect British influences but also reproduce what was deemed to be British elegance.

Indeed, the guiding hand of memories of home that were quite likely to have been idealised or confected were apparent from the earliest days of settlement, particularly evident among the privileged elite since poor battlers, if they were able to garden, toiled principally in sustenance gardens.

But the truth was that while life in the new land was crippling, for some it offered hope and new directions for others. Many an emancipist was able to make good in these changed circumstances, putting down roots and building a sense of place in the new land.

On a grander scale it is revealing how relatively privileged settlers could seize opportunities to establish themselves as persons of note in the colony. And this applied to many whose names are historically familiar, people such as Macarthur and Wentworth. I was taken by the story of Edward David Stuart Ogilvie who, blessed by birth from a comfortable enough albeit not elite background was, through hard work and good luck, able to transform himself into a gentleman of substance and influence. Just look at the transformation in his domestic setting. His early homestead and its curtilage at Yulgilbar in New England (ca 1850) appear quite modest, not so the mansion and cultivated landscape at Yulgilbar ten years later. Insert image . No modesty here in the house and sweep of garden and grounds.

But if ever sentiments evoked ‘home’ as the past in another place, it is those of Rachel Henning:

…I do not care enough about the Australian flowers to take much trouble with them. I often wonder what can be the difference. I suppose it is the want of any pleasant associations connected with them. I often see very pretty flowers in the bush and just gather them to take a look at them, and then throw them away again without any further interest, while at Home every wildflower seemed like a friend to me.

Rachel’s views changed over time, transformations that were closely linked to a series of moves through which she expressed her sense of self and place. After years living in the Stroud area, but not in her own place, she moved to the Illawarra –– a landscape she reported as lovely, that provided the opportunity to garden as she wanted. True, moving there with her husband where they owned their own land would have been a strong contributing factor to a sense of attachment, but that notion of belonging comes with the development of a strong relationship to place –– so clearly established in making a garden.

What was, in essence, a great social experiment by the British Government is the backdrop to all these ten essays. There was no existing social framework into which to introduce convicts, administrators, a military presence and free settlers. The template for settlement was British but there was no defined social context in which to slot or adapt this model. In a way the essays reflect this apparently blank canvas in their broad-ranging approaches to the significance of gardens and garden-making in the development of the settlement.

Colleen Morris (‘Planting New South Wales’) looks to the role of the Botanic Gardens in forming landscapes that reflect a complex history. It is worth recalling that the Botanic Gardens were established in 1816, quite early in the colony’s history and that we celebrate their bicentenary this year.

Colleen points out that ‘…one of the roles of the Botanic Gardens was to act as an experimental and acclimatisation garden for potentially commercial agricultural and horticultural producers while propagating young plants to be “despatched”, with charge, to the colonists who requested them.’ Inevitably, in a common enough pattern, benefits of this system went to the major landholders, although when Charles Moore became Director in 1848 things changed. And it is at this point that the imprint of the Gardens (principally under the guidance of Moore and his successor J H Maiden) can be seen to have made such an impact on the landscape of New South Wales: this is because parks and public spaces (and private too) were planted out with what were the favoured varieties distributed through the Botanic Garden. Moore, for example, was particularly drawn to sub-tropical trees and plants and Maiden to native forms. Plantings in the Botanic Gardens dating from 1862 reflect the sub-tropical theme followed by emphasis on native forms.

Today the landscape bears witness to these changes but, as you know, gardens are living sites; over time the plants in them grow, reproduce and die. Some are deemed to have historic and heritage value and steps have been taken to preserve them. But recognition of their value doesn’t always ensure their security. Certainly, if the general character of the place is not lost then its historical significance stands a better chance of being protected. Such is the case with Retford Park in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales.

Sue Rosen narrates the evolution of this property over time. She points out that it has become reduced in scale and that while many of its elements –– architectural, sculptural and planting palette –– have been destroyed, or at least modified, nonetheless, taking account of its historical themes, it retains its cultural and historical significance so that much of it is valued in heritage terms. At the time of writing this essay she foreshadowed the conservation of the house and park as a whole. This is precisely what has since been legally and administratively put in place as James Fairfax –– owner of many years –– recently handed over Retford Park to the National Trust to ensure its safe-keeping, escaping the destruction that Stuart laments. It is interesting to note how much of the British heritage remains, notwithstanding the incorporation of indigenous elements that, ironically, appear in the garden as exotics.

While botanists were certainly intrigued by these novel native forms and took great care in despatching samples of them to Britain (the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew was a significant repository) initially they held little interest for settlers generally. Despite a European fascination for new plant forms, for decades colonists were leery of native vegetation. Unfamiliarity bred suspicion and anyhow reproducing, as best possible, known forms, and the aesthetic of the old world, no doubt softened the pangs of nostalgia, a balm that kept alive memories to be cherished. But the reality is that while the gardens of the old world continued to have primacy in the hearts and the imaginations of gardeners, over time, indigenous forms also took their place, a rich palette reflected in contemporary gardens that have also benefited from introductions from other parts of the world.

In her chapter Sybil Jack tracks the spread of plants –– new and old –– in the expanding settlement. Initially the Governor’s garden was a source of stock. Again questions of privilege surface as ‘respectable settlers’ appeared to be favoured in the distribution.

But, from an early stage enterprising men were advertising plants for sale, although most were well beyond the purse of the average colonist. As the century wore on some settlers, with an eye for the commercial returns, seized the moment and established nurseries –– some on a large scale. And it was from the mid 19th century that nurserymen were producing catalogues that showcased new and popular plants to a wide population.

Harking back to Ailsa’s chapter on exhibitions, it was also the case that horticultural exhibitions provided a means of promoting gardening and demonstrating social worth.

Several of the essays have as a theme gardens as sites promoting health, and Janet George’s first career as a pharmacist steers her in this direction. In her chapter ‘Cultivating Wellbeing’ she tells a story of the important medicinal and therapeutic role of gardens in the settlement.

From the beginning a good diet and food producing gardens were recognised as critically important. Beyond sustenance gardens, however, growing medicinal plants was recognised as the primary source of medicines well into the 19th century. As Janet writes, the colony was established at a time when botany and medicines attracted great interest and research and theories of health, ill-health and its treatment became more sophisticated with medicinal plants grown commercially and therapeutic gardens attached to institutions increasingly regulated. Yet over the decades folklore and old remedies remained central in a good deal of medical practice, as they did in the community.

Happily many of the plants had utilitarian value as well as being decorative, making them quite desirable introductions into a garden. Take, for example, foxglove, identified as useful in treating heart diseases, as were a whole lot of other plants known to have therapeutic qualities – garlic, horehound, geranium, cinnamon, liquorice and so many others. But what is revealing is that it took a very long time until there was any transfer of indigenous knowledge. It was rather later that the Botanic Gardens, through the agency of J H Maiden, supported the economic development and use of native plants. Although some, with an eye for commercial advantage, could see their potential. For instance in quite early days Thomas William Shepherd saw an economic future in the production of essential oils derived from eucalyptus.

It is through the lens of disease that Catherine Rogers approaches the theme of the book, tracking a transformation from those spaces known as ‘backyards’ to gardens. She takes a case study in Burwood to reveal how that domestic space (the backyard) was a ‘place in which the practical realities of daily life were visible and also kept hidden’, even in relatively well-off comfortable suburbs. Those practical realities included the disposal of rubbish and human waste

Around the mid 19th century city dwelling was associated with poor health. Stories of diseases and environmental ills resulting from overcrowding, lack of services and poor building were rife. In contrast, new suburbs ‘effectively located in the country were presented as healthy, natural places’ and open for development. But, and here is the paradox, Catherine tells the story of how the apparently desirable suburb of Burwood soon became a health concern. Actually the sanitary state of the area behind the house was little better than the crowded living of the city, bringing disease to the suburb. With no planning directives it served as a work area that also housed cesspits and rubbish piles and general household waste. There was virtually no drainage so that the effluent of adjacent dairies and small farms flowed across back yards. But epidemics threatened and authorities were forced into action. Over time regulations were introduced covering various services: drainage systems, piped water and removal of backyard cesspits. These changes were significant in how the backyard was used and how it appeared. It could now be reimagined as a site of family leisure and pleasure. But this transformation did not occur overnight as a picture of Alice in her backyard attests. With some evidence of a worksite in the pile of stakes, as Catherine points out it was not yet a location befitting Alice’s elegant garb.

Then on to John Ramsland’s essay. He also draws on the remarkable growth of the population of Sydney in the late 1800s that saw Sydney as a city in transition. While the suburban movement was taking off, as he writes: ‘The poor were left to rot in the older inner-city suburbs of street terraces and gloomy laneways where doors opened directly onto the thoroughfare.’ His description of these filthy, unsanitary conditions is quite long and very powerful and it was these surroundings that were deemed by middle-class reformers as the ‘root cause of immorality, ill health and social discontent and unrest.’ It was from this ground that the garden-suburb movement took shape. There is a sticking point however because, whether the developments were born of private enterprise or government policy, the working-class people, who lived in these mean streets, were not usually consulted about what was deemed as good for them.

John unpacks the social and political history of the development of the Dacey Garden Suburb. Named after a Labor Frontbencher in the New South Wales Parliament – John Rowland Dacey – the estate was to be built on 400 acres of sandy wasteland and catered for ‘respectable working classes’, that is, those people considered worthy of that ‘improving’ relocation.

Another garden village – at Matraville – took shape considerably later. Identified as the only garden village in the world to do this, it was proposed to settle soldiers maimed in World War 1, rescuing them from the mean streets of Sydney. Again while gardens were hard to establish on such a windswept tract of land, slowly they did. One of the negative consequences was that it separated the community of disabled diggers from the rest of society, effectively quarantining them; another was that the project became a political football. The garden village did not ultimately survive the predations of development.

What is quite evident in all these essays is that gardening is an exercise in control, and Gaynor Macdonald’s opening chapter spells this out quite clearly. As an anthropologist Gaynor is concerned with the cultural and social dimensions of the meaning of gardens. She describes the landscape of Japan as imbued with great spiritual power, a power that is unpredictable and uncontrollable. In their meticulousness Japanese gardens mediate the relationship of people and the wider environment; they capture in microcosmic form that natural environment, and in doing so exercise control over it. The tranquil and disciplined gardens may look beautiful but, much more than that, these gardens symbolically express control over the unruly and unpredictable environment. As Gaynor writes: ‘…they separate order from disorder’.

How stark is the difference between this approach and the traditional view of Aboriginal people of their world. Here the landscape is, in essence, a garden; not one that is owned but one in which Aboriginal people are intimately connected in spiritual, social and material terms. Their cosmology brings together humans and their environment in a kin-based, spiritual system. In accordance with the blueprints of cosmology, laid down by their spirit ancestors ‘Spirits and people worked together in maintaining the balance of life: rituals were focused on the nurturing, cleansing and regeneration of all the flora and fauna belonging in their garden.’ In this system they tended their entire country as a garden. This is a garden, a park, an estate, in its most expansive form, an outcome of active and ongoing cooperation between people and creator spirits.’

Let me return to the thoughts that I expressed at the beginning of this talk: that gardens do not mean the same thing to all people. For a start society is not of a piece – there are social class differences, age differences, gender differences, and a myriad of different backgrounds laced through all this. Highly unlikely that we will all look at gardens in the same way. Moreover think of the way social change has impacted on our attitudes: over time models of what constitutes a family have shifted and that has consequences for the way we live in houses and gardens. Then there is the way that landscaping and plants themselves come in and out of fashion. I spoke recently of how gerberas were of the moment in my grandparents’ garden, only to disappear and more recently make a comeback. The same might be said of the guest appearances of succulents. And where have the frangipanis gone? Or the pointsettias? They are there but in diminished numbers. I have no doubt you will be able to add significantly to this list

I understand that your Society feels keenly about recognising the place of gardens in local history and I applaud you for that. And we can take that approach further. I hope that this overview of the contents of Gardens of History and Imagination not only indicates the significance of gardens and garden-making in the history and development of the colony of New South Wales but also some of the many prisms through which we can look a this history. I also hope that, wide-ranging as the collection is, the strong connecting themes and threads are clear of how, through gardening, people can create a sense of identity, as individuals and as a society.

Gretchen Poiner November 2016

Image 29 ‘Henrietta Villa’ Clear views to and from the villa, from the harbour and from the kitchen gardens. (Stuart)