Ian Willis

In late August 1914 the Sydney newspaper the Sunday Times (30 August) described Red Cross volunteers as the ‘Angels of Mercy’, and Red Cross volunteers would ‘Stretch forth your hands to Save!’ Red Cross nurses, according to the report, had the touch of Christ, were willing to stand ready to ‘succor and tend the men laid low in the country’s service’.

In July 1914 Lady Helen Munro Ferguson, the wife of the Governor General and founder of the national Red Cross, at a Double Bay Ambulance Class held in a St Mark’s school room at Darling Point in July 1914, referred to Red Cross volunteers as ‘ministering angels’. This was an allusion to a Biblical passage,(New International Version Bible) Hebrews 1:14

Are not all angels ministering spirits sent to serve those who will inherit salvation?

In this context it could be interpreted as meaning that Red Cross workers are sent forward to provide aid or assistance to others in need with a strong moral overtone.

The Red Cross ‘Help’ poster was drawn by artist Scottish-born David Henry Souter, who settled in New South Wales in 1887 where he worked as a journalist and illustrator for books and magazines, including the Bulletin, and was one of the first artists to start designing Australian posters. The aim of the poster was to inspire Australian women to support the war effort. [1] The poster features a nurse in a stylised Red Cross uniform standing with her arms outstretched, as if appealing for help, in front of a red cross. In the background is a ship, an ambulance and a field hospital displaying the Red Cross emblem.

The Red Cross as a metaphorical mother is present in Red Cross literature from as early as December 1914.[2]

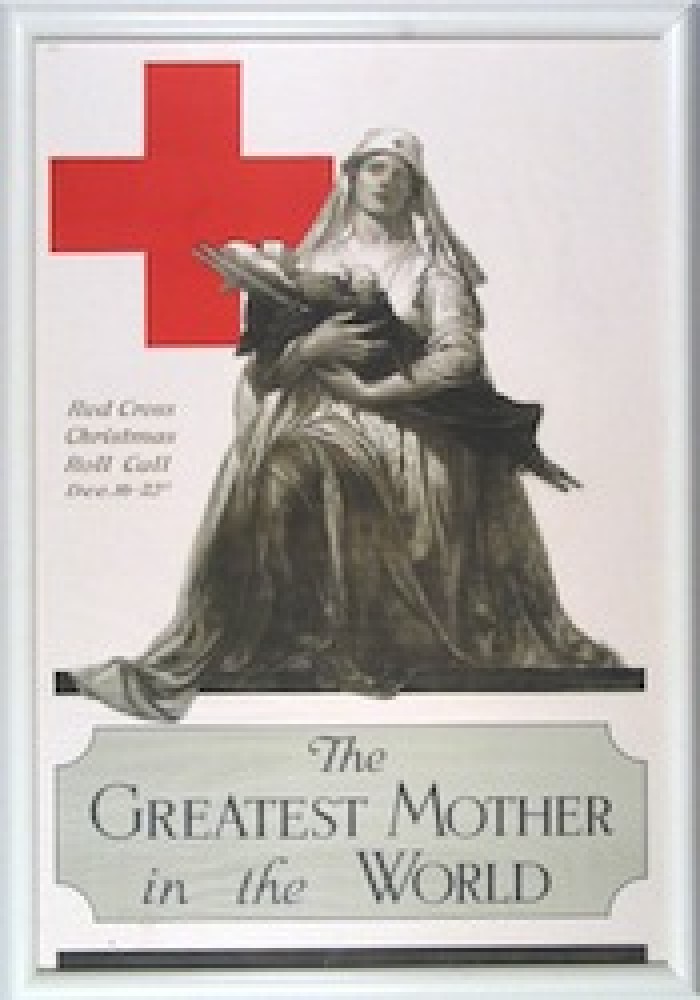

This issue has been examined by Canadian historian Sarah Glassford in her work on mothering and the Red Cross. She has looked the use by AE Foringer and the 1918 poster used by the American Red Cross entitled ‘The Greatest Mother in the World’. She analyses in her account how the poster uses ‘two potent images of Christian iconography: The Virgin and the Child’. She argues that the use of the mothering metaphor and ‘care work sick and wounded citizen-soldiers in terms of mothering…bestowed that work with symbolic and moral power’.[3]

Red Cross volunteers and other Edwardian women saw social action as an alignment of patriotism, duty, class, gender, Christianity and motherhood. After 1914 the Red Cross leadership at all levels of the organisation wrapped these characteristics together and promoted the society to volunteers and the community as the soldier’s metaphorical ‘mother’ and guardian angel on the battlefield. The Red Cross was identified in posters and other publicity as ‘Red Cross, Mother of all Nations’, and as the ‘Greatest Mother in the World’. [4] Kate Egan, the organiser of the packing department of the New South Wales Red Cross, maintained that the Red Cross was ‘stretching forth her hand to all in need...[s]he’s warming thousands, feeding thousands, healing thousands from her store, the greatest mother in the world’. In 1919 the Brisbane Courier ran an article in Red Cross week under the heading ‘The Mother of Soldiers’ and stated that the Red Cross was ‘the great mother who stretches forth her hands to all in need, warming thousands, feeding thousands, healing thousands from her store’. A ‘Soldier’s Mother’ wrote in 1918 that the ‘Red Cross is the greatest mother in the world, stretching forth her hands to all in need’. A Sydney Morning Herald correspondent referred to the Red Cross as ‘the great soldier’s mother’. On Red Cross Button Day in 1918 the three designs for sale for 1/- were ‘The Greatest Mother in the World’ , ‘The Soldiers’ Friend’ and an image of ‘a Red Cross nurse with an outstretched hand’.[5] Mary McAnene, who was a nurse at No 3 Australian General Hospital at Lemnos and matron of Camden District Hospital before joining up, maintained that

It would be a sorry day for the boys when they get their knock if it were not for the Red Cross; the military authorities are like a father to the lads, but the Red Cross is like their mother.[6]

The Red Cross as mother and guardian angel was an extension of the notion around the ideology of motherhood which was an integral part of women's service role in the British Empire, according to historian Anna Davin. The ideology of motherhood stated that women had the duty and destiny to be the 'mothers of the race'. Child-rearing was a national duty, and good motherhood was an essential component in the (eugenist’s) ideology of racial health and purity. The family was the basic institution of society and women's domestic role remained supreme. By the inter-war period pre-occupation with the family and motherhood had turned these traits into a national priority for the British race. Imperial motherhood was promoted as a scientific necessity and a patriotic duty.[7] There were concerns over the decay of the home and family life expressed by a number of British women's groups, especially those associated with evangelical Christianity, including the Mothers’ Union (MU), the National Council of Women, and later the Women’s Institutes, the Country Women’s Association (CWA) and Red Cross. These voluntary organisations provided a training ground for middle class women and allowed them to gain a 'public persona' while upholding the 'values of both middle-class femininity and bourgeois respectability'.[8]

So to sum up, while the imagery of motherhood was romantic and sentimental the Red Cross organisation during the First World War was able to effectively to use this iconography to encourage strong community support for their activities. By the end of the war the Red Cross owned the homefront war effort across the state. For many women and the community in general helping the war effort meant helping the Red Cross and for them the Red Cross worker was the soldier’s guardian angel.

Extract from presentation to ISAA-NSW Work-in-progress workshop on 5 August 2015.

For more information about Red Cross see https://www.academia.edu/8017255/Ministering_Angels_The_Camden_District_Red_Cross_1914-1945

[1] See more at: http://blog.perthmint.com.au/2015/01/09/iconic-red-cross-poster-portrayed-on-world-war-i-commemorative-coin/#sthash.74VwqSoT.dpuf

[2] The NSW Red Cross Record, December 1914, p.19

[3] Sarah Glassford, “The Greatest Mother in the World”, Carework and the Discourse of Mothering in the Canadian Red Cross Society during the First World War’. Journal of the Association for Research of Mothering, Volume 10, Number 1, p.220

[4] National Library of Australia, War Posters, Lithographs, 1918.

[5] The Camden News, 19 September 1918; The Brisbane Courier, 26 July 1918; The Blue Mountain Echo, 19 July 1918; The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 February 1919; The Mail (Adelaide), 7 September 1918.

[6] The Camden News, 27 June 1918.

[7]. Anna Davin, 'Imperialism and Motherhood'. History Workshop, 1978, Volume 5, Issue 1, p. 13.

[8]. Clare Wright, 'Of Public Houses and Private Lives, Female Hotelkeepers as Domestic Entrepreneurs'. Australian Historical Studies, Volume 32, Issue 116, April 2001, p. 69.